The Peacock’s Excuse

Hamid Shams

Curator: Marie Canet

February 4th - April 1st 2022

The peacock in particular claims he is expected elsewhere - in paradise, whence he was exiled, having introduced Satan there in the guise of a seven-headed snake. He refuses to join in the adventure on the grounds of his uniqueness. The hoopoe refutes his argument, calling into doubt, as for the other desistors, his ability to fly. She urges him, instead of making up fake excuses, to conquer the serpent of pride, cowardice, and illusions, so he may unlock the spiritual secrets and return home to paradise.

In his installation The Peacock’s Excuse, on display in the Pejman Foundation: Kandovan Building, artist Hamid Shams refers directly to Farīd ud-Dīn ʿAṭṭār’s text. Indeed, we enter the building through an architectural labyrinth that recalls, life-size, the hide-and-seek complexities Attar conjures up for his readers. The recalcitrant birds of the parable cover the outside walls of the structure, in large engravings on metal and in a style recalling traditional Persian miniatures. In contrast, the inside, which can be reached in various ways, is decorated with low-relief designs. The spiritualist birds, the hoopoe’s followers, seem glued to the walls, covered in high-gloss, vinyl-like black resin.

Shams’s work pays tribute to Aṭṭār’s poetry and the art of indirect allusion that characterizes the language of the parable: the poem is an allegory studded with images offered up for meditation and open to interpretation. It explores the formal possibilities of combining various literary registers: dialogue, storytelling, metaphor, and so on. Indeed, ʿAṭṭār himself advises his readers to study the work several or even a hundred times or more, as each reading will offer a chance to discover new images and new meanings, as in a labyrinth.

Just as it is a challenge to find our place in the metaphorical maze of the text, so it is hard to plot our path through The Peacock’s Excuse, which is developed over three floors of the Kandovan Building. Shams transforms the building into a ‘language space’ designed to bind cryptic forms together into a network. Like the poem, the building is a labyrinthine structure where the poetry of words (inscribed on mirrors or enclosed in the walls) and of bodies (experiencing the sensations of height, changes of level, angles, and depths) interplay.

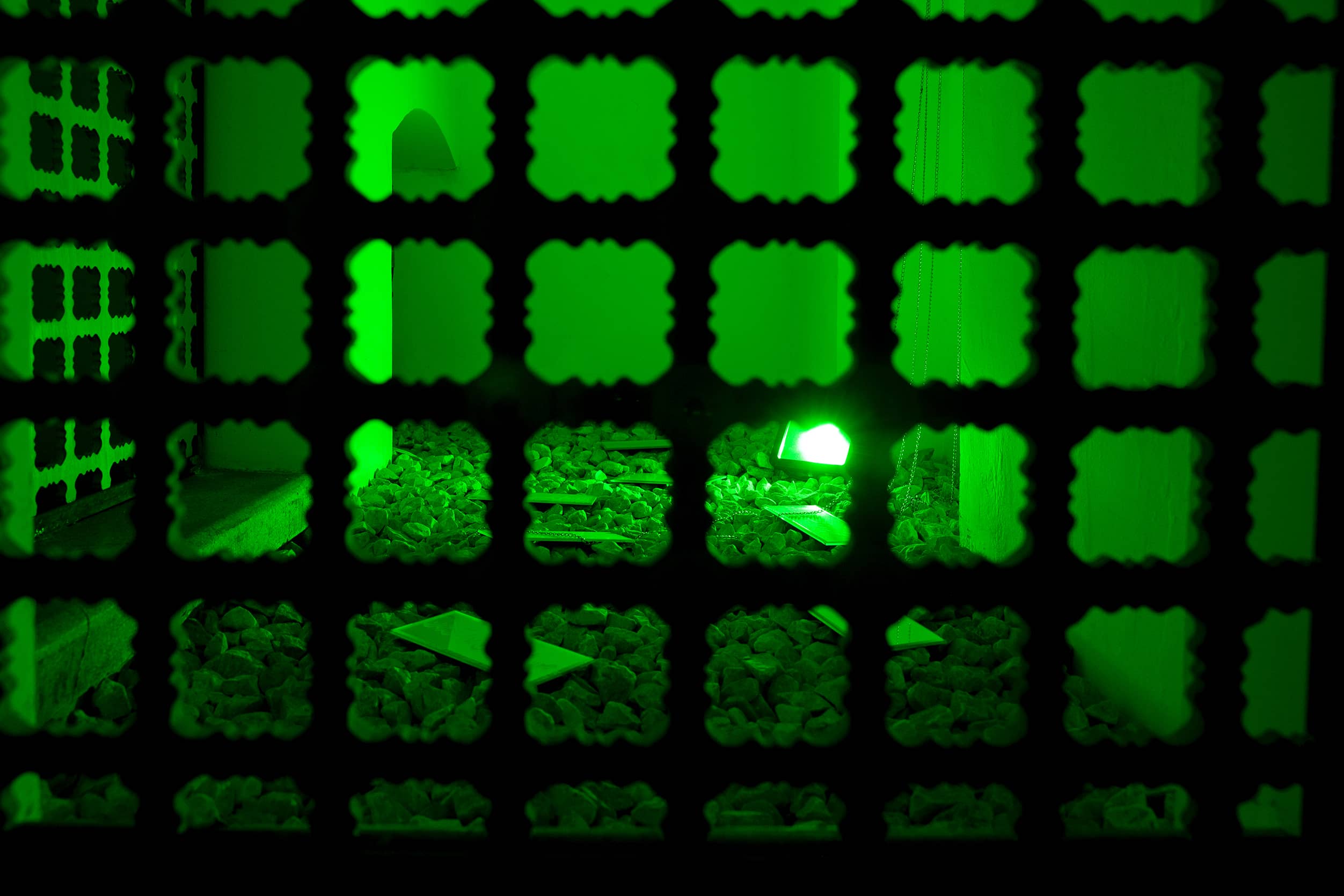

Shams heightens these visual, sensual, and intellectual dimensions, proper to Persian poetic culture. The work is unfinished; it is up to the viewer to complete it. Like poetry, it is to be pursued. That is our task, in the artist’s own words. The whole building is a text waiting to be activated. Some of the forms are even stored away in wrapping, such as the urinal in the basement (Piss, 2022); others remain unfinished, like the sculpture Sling (2019): all that's left are the chains hanging from the ceiling in an alcove. Here, red light, symbolizing fire, floods the space; there, green light, symbolizing the spiritual, seeps through two openings.

From the basement to the first floor and back again, our senses are in transition. It smells of metal, plastic, rose water, or stone. The artist would have liked, he says, to wrap everything there, so that our circulating bodies would be confronted - like the birds on the voyage - with a reality that seems to escape us. There is, however, no water in the fountain (Black Flower, 2022), as if language, despite all the variety and possibilities it offers, were lacking in fluidity, incapacity, as if too closely bound up in the functional, informative, and political uses modernity demands of it.

Marie Canet

Hamid Shams (born in 1990, Tehran) lives and works in Paris and is a graduate of the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in the Department of Photography and Film. Inspired by Persian poetry and literature, he produces works with a focus on storytelling and uses different mediums like installations, painting, photography, and film to produce them. Hamid Shams introduces "relationships and violence" as the main idea behind the creation of his works.

Date and Location:

Pejman Foundation: Kandovan Building

February 4th - April 1st, 2022. 4 - 8 PM